Shaping the Vertebrate Brain

By Dr. Alex Dornburg

Our daily lives have a rhythm. We sleep around certain times. We wake up at certain times. We eat around certain times. This rhythm of life is not unique to humans; organisms everywhere follow its beat. Think about it; you are far more likely to see a robin at noon than a raccoon or owl. Some animals are nocturnal, others are not.

These biological rhythms are extremely important for the health of both humans and wildlife. Long-term disruptions of these rhythms lead to everything from loss of cognitive function to increased risk of heart disease and certain types of cancers. Given the importance of biological clocks in cognition and other aspects of human brain function, this raises a question:

How have evolutionary changes in animal activity cycles shaped the vertebrate brain?

One group of animals to look for answers to this question might surprise you: fishes.

Fishes constitute approximately half of the vertebrate species on earth, and possess a remarkable diversity of brain sizes and shapes. If you have ever spent any time on or in the ocean at night, you are likely also aware that there is often a major shift in which fishes are awake at different parts of the day.

Numerous marine fishes are truely nocturnal, often possessing massive eyes (think squirrelfishes, soldierfishes, sweepers, or the aptly named bigeyes). The visual system of these large-eyed denizens of the dark stands in stark contrast to the often small eyed species active during the day.

A squirrelfish, one of the many species of large-eyed reef fish that come out at night. Photo: A. Dornburg

The contrast between daytime and nighttime active marine fishes creates a great natural experiment from which to investigate general patterns of vertebrate brain evolution. We did just that.

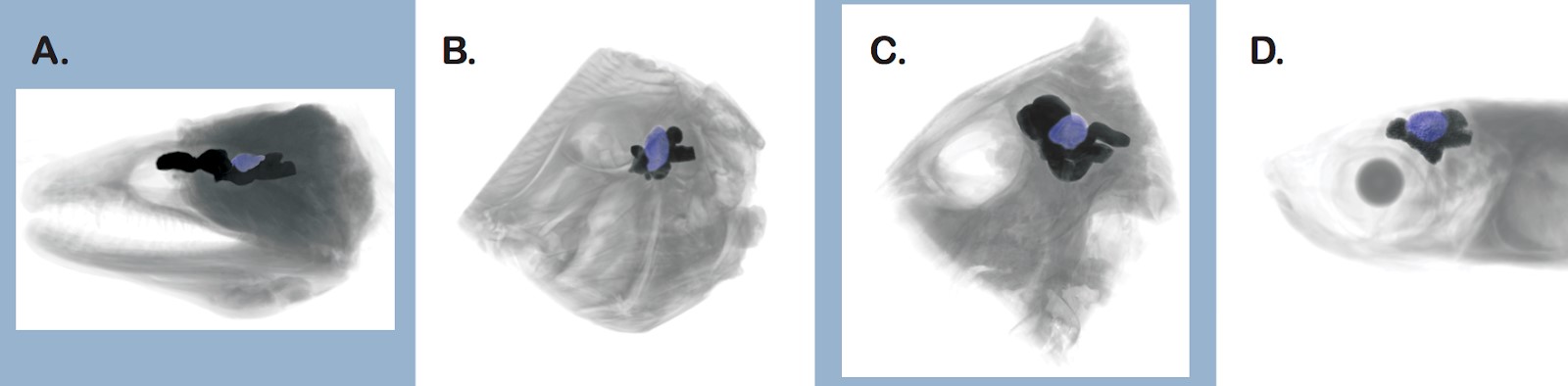

Using cutting edge micro-computed tomography (CT-Scan) imaging similar to what you might find in many hospitals, we built 3D scans of the brains of dozens of nighttime and daytime active fish. Using measurements from these scans in conjunction with ecological, morphological, and behavioural data, we developed a new perspective on how changes in activity patterns shaped the evolution of the visual processing centers of the brain.

Images of fish brains scanned in our work with the visual processing region colored in blue. A. Moray Eel. B. Peacock Flounder. C. Triggerfish. D. Silverside. Images taken from Iglesias et al. 2018.

Becoming nocturnal results in a loss of investment in parts of the brain devoted to processing visual stimuli, despite the evolution of massive eyes that maximize light collection.

So who invests the most in processing visual information?

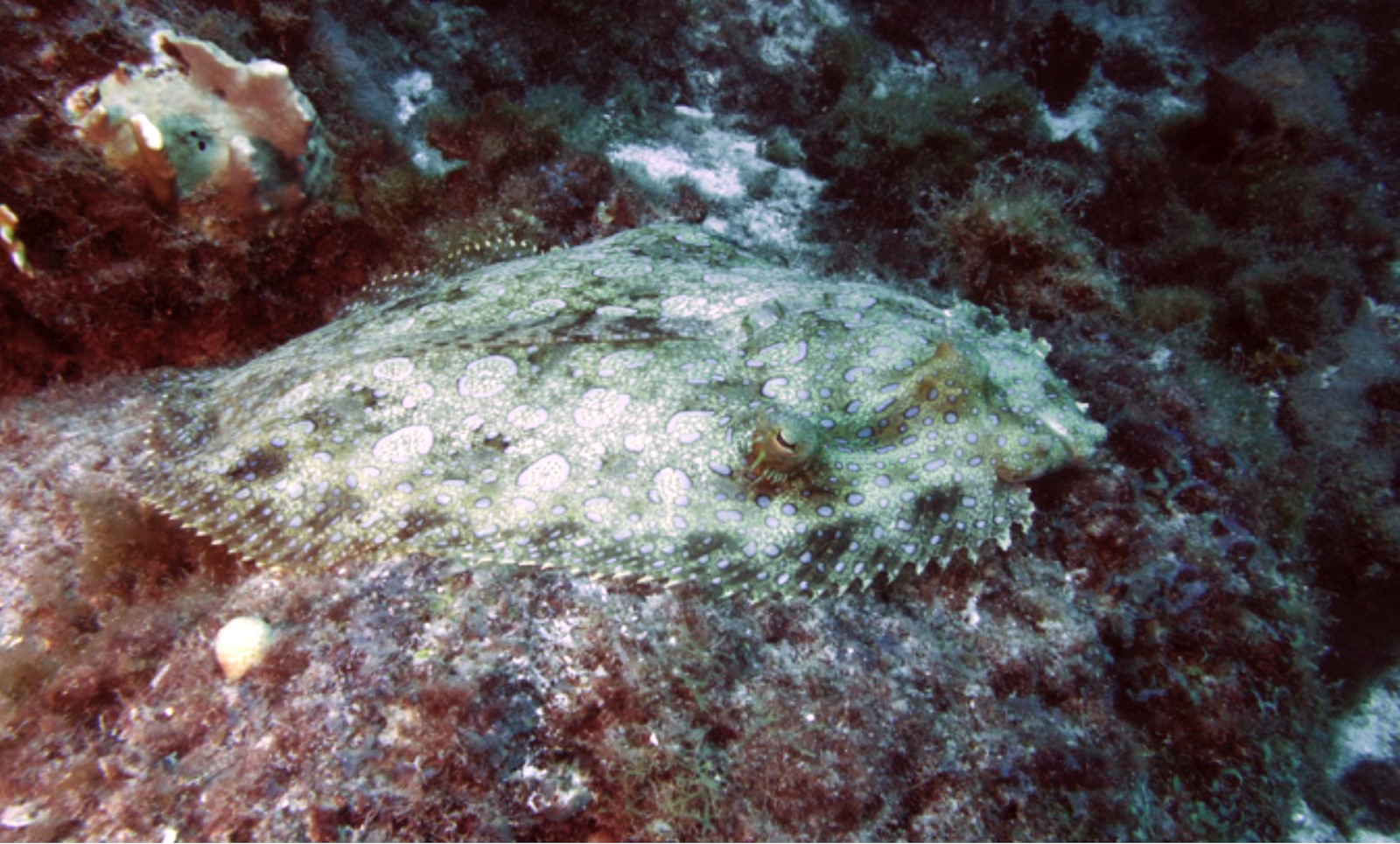

The answer was surprising: reef-associated flatfish. Flounders such as the peacock flounder have massive visual processing centers, likely as a result of their ability to camouflage in complex reef environments.

Peacock Flounder in Curaçao. Peacock flounders have some of the largest visual processing regions of any marine fish and are masters of camouflage. Photo: A. Dornburg.

Another surprising result was that nocturnal open water feeders vulnerable to predation also had increased investment in brain tissue for visual processing. Predation pressure has been repeatedly hypothesized to drive changes in the evolution of the brain, in particular cognitive ability. Our results here lend more support to these ideas, suggesting that millions of years of predator-prey interactions have had a major role in shaping the way animals, including ourselves, experience reality.

More broadly, our findings illuminate the deep impact that circadian rhythms have had on the evolution of the vertebrate brain. As we continue to alter the face of our planet, these results have major conservation implications. Light pollution and human activity patterns around the planet are altering the times when wildlife is active. Our results suggest that continued environmental changes that disrupt or alter animal activity patterns could drive major, unintended, neurological changes in wildlife over the next century.

Our alteration of light cycles changes the natural rhythms of wildlife, both on land and in water. Our work suggests this could have a profound impact on the evolutionary trajectory of a species’s brain. Photo: A. Dornburg.