Game of Poisons

November 27, 2017 by katerinazapfe, posted in Australia, Deep sea, Future Frogmen, Marine Science, Oceans deadliest, Octopus

Poisons have fascinated humanity for centuries, and some of the top contenders for world’s deadliest come from the sea. Killer chemical cocktails have evolved independently throughout the Tree of Life, and serve as fast and effective means to capture prey and evade predation. Poisons can be classified in a variety of ways, including by severity, by which body system they target, and by the method of delivery.

In biology, one common distinction between substances is poisons and venoms. Toxins that enter a victim through skin contact or ingestion are generally labeled poisons, while those that operate through the circulatory system are referred to as venoms. This common distinction explains why a sea krait is referred to as ‘venomous’ while certain nudibranchs are labeled ‘poisonous’. The game becomes even more intricate as players display warning colorations to signal inedibility, mimic warning colorations of others with convincing accuracy, and develop chemical tolerances in an arms race for species survival.

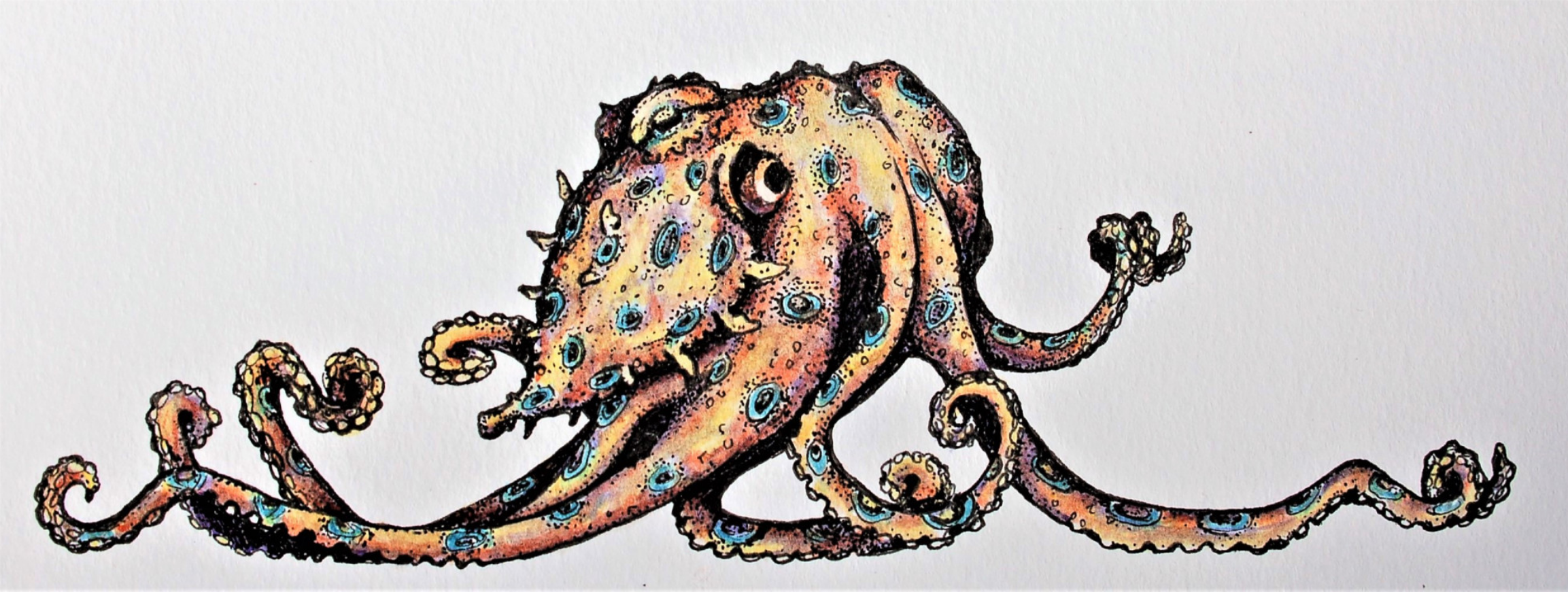

Many animals use poisonous chemicals to both hunt and avoid being hunted. One such small, inconspicuous sea dweller has partnered with an important strain of bacterium to make the charts of ‘ocean’s deadliest’. Thanks to this commensal partnership, the shy blue ringed octopus hides among cover in Australia’s shallows hunting for food, taking down small crustacean meals with ease. The secret lies in its venomous saliva, laced with powerful tetrodotoxin and formed within internal ducts by the bacterial colonies. The formidable neurotoxin, TTX, can be found in a handful of marine life, and is named for the order Tetraodontiformes. TTX attacks the victim’s nervous system, inhibiting signaling and voluntary muscle movement. Additional symptoms vary from vomiting, breathing difficulty, and in serious cases respiratory failure and subsequent asphyxiation depending on the amount of venom transferred. The toxin has no known cure, though people can sometimes be saved through artificial breathing. The bites are often small and subtle, and there is speculation whether one actually needs to be bitten to facilitate toxin transfer or if prolonged skin contact could be enough to warrant concern.

Despite the fear this might instill in some, the octopus, however, is not out to inflict any harm on human beach goers. Its venom serves as a powerful hunting tool, quickly subduing prey that might otherwise cause harm to the octopus in a struggle. Occasionally, a determined predator may ignore the warning colors of the soft, snack-sized octopus and provoke a bite. But thankfully, when given the option, it would rather go about its daily hunting and hiding rituals, only flashing the telltale blue rings when agitated enough to remind the world once again of its secret weapon.

#futurefrogmen, #octopus, #oceansdeadliest, #australia